Activists and preservationists are changing the kinds of places that are protected—and what it means to preserve them.

No one knows what happened to Gabriel’s body. Born into slavery the year his country declared its freedom, he trained as a plantation blacksmith and was hired out to foundries in Richmond, Virginia, where he befriended other enslaved people. Together, they absorbed, from the revolutionary spirit of the era, ideas of independence that were never meant for them. Gabriel kept hammering out whatever his masters demanded, but in secret he began to forge a network of thousands of enslaved and free blacks who planned to rally under a flag stitched with borrowed words: “Death or Liberty.” But a terrible thunderstorm flooded the roads on what was to be the day of their revolt, in August, 1800, and during the delay two of the conspirators betrayed the rest. Within a few weeks, twenty-six of them were hanged. Gabriel was executed less than a mile from the church where Patrick Henry spoke the words that inspired what would have been their battle cry. Some historians believe that Gabriel’s body was left in the burial ground beside the gallows, where it would have joined thousands of other black bodies that, consigned to the bottomland of the city, washed into Shockoe Creek whenever it rained.

Shockoe Bottom, as that valley is known, was the center of Richmond’s slave district. In the three decades before the Civil War, more than three hundred thousand men, women, and children were sold in Richmond, the second-largest slave market in the United States. Not every enslaved person who passed through left the city; many were made to work in its tobacco warehouses, ironworks, and flour mills. Between 1750 and 1816, most of the African-Americans who died in Richmond were interred in what was known as the Burial Ground for Negroes. After that, the graves at Shockoe Bottom were abandoned, and residents claimed more and more of the land for themselves, ignoring the coffins and bones. The city turned what was left into a jail, and then a dog pound; later, state and federal officials carved I-95 through its center.

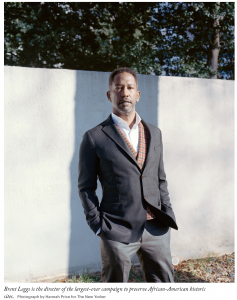

“I remember thinking there was nothing left,” Brent Leggs told me recently, of his first encounter with Shockoe Bottom. Leggs, the director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, is typically contacted to help preserve something, even if it is only a crumbling foundation. But in Richmond he was called on to help save what no longer exists.

The first wave of protests began in 2002, when Shockoe Bottom was still a parking lot. Community groups like the Defenders for Freedom, Justice & Equality organized to reclaim the burial ground and memorialize Richmond’s connections to the slave trade. The Defenders held walking tours, educational forums, and vigils at the site. Activists demanded that the city “get your asphalt off our ancestors,” and, although it took a decade, the pavement was eventually cleared. In 2013, the group helped launch another wave of protests after the city proposed building a minor-league baseball stadium at Shockoe Bottom, which would have destroyed what archeological evidence remained and would have desecrated the burial ground. That was when the National Trust stepped in.

Please CLICK HERE to continue reading the article on AAAM long-standing member and supporter, Brent Leggs.